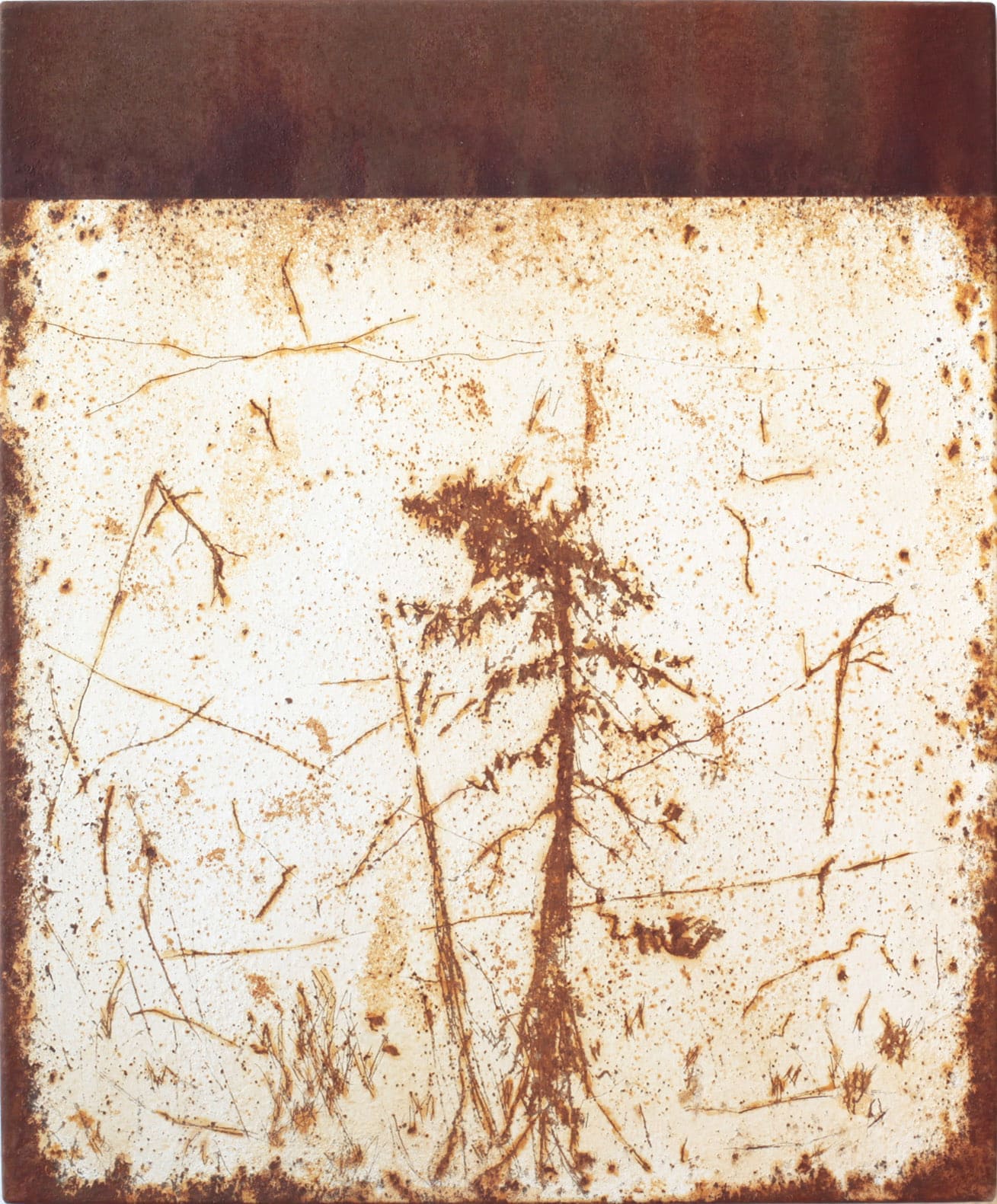

Huellas del paraíso

Manuel Velasco

More information about

(Pre)visions of an Immediate Future: The Eden Behind the Curtain.

We love that dim clarity, made of outside light and uncertain appearance, trapped on the surface of twilight-colored walls and barely holding on to the last remnants of life. For us, that clarity on a wall, or rather that semi-darkness, is worth more than all the decorations in the world, and its sight never tires us.

Junichirō Tanizaki. Praise of Shadows. 1933

In the final pages of The Map and the Territory (2010), Houellebecq has a vision. The future of the Ruhrgebiet appears to him as follows: ‘From Duisburg to Dortmund, passing through Bochum and Gelsenkirchen, most of the old steel factories had been transformed into exhibition centers, theaters, and concert halls, while local authorities tried to establish industrial tourism based on the reconstruction of the working-class lifestyle from the early 20th century. In fact, the whole region, with its blast furnaces, its “escorials,” its abandoned railways where freight cars were rusting, its rows of identical and fairly neat barracks, sometimes adorned with factory gardens, resembled a conservatory of Europe’s first industrial era. Jed had been struck by the threatening density of the forests surrounding the factories after barely a century of inactivity (…). Those industrial giants, where the bulk of Germany’s productive capacity had once been concentrated, were now rusty, half-destroyed, and the plants had colonized the old workshops, infiltrating the ruins and gradually enveloping them in an impenetrable jungle.’

The parallelism between this Houellebecqian premonition and the one materialized in Huellas del paraíso is very evident: not only does the landscape – nature, considered here as an allegory of Eden – seem to emerge spectrally from those backgrounds of rust and paint so characteristic of Manuel Velasco’s work, as well as from the aesthetics of the industrial – what better image of declining industry than the chipped paint on a door or a rusted sheet-metal machine – but the artist, whose studio is in La Marina del Prat Vermell, waits resignedly, in that old industrial area of Barcelona whose decline dates back to the 1960s, for the inevitable demolition of the entire neighborhood. The Ruhr factories will probably suffer the same fate: what Houellebecq describes is only a dream.

The Eden Behind the Curtain, therefore, as that was the title of Manuel Velasco’s latest solo exhibition at the Sala Parés. Resquicio (2022) was a tough exhibition. The beginning of the series dates back a few years and takes place at a difficult moment for the artist and humanity: barely a few decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, new walls even bigger were rising – the one separating the Sahrawis from Morocco is over 2,700 kilometers long, the one in the West Bank, over 700… but above all, as a consequence of the rise of new powers – and the subsequent decline of the old ones – a movement of retreat, distrust toward foreigners, and the defense of identity was forged in Europe and North America during those years, a movement that has exploded, as we can see, over these last months. Manuel Velasco then began working with iron dust – a material used in the steel industry and in agricultural product processing – which he continues to develop. At first, those rusty surfaces, occasionally perforated as if they had suffered bullet impacts, resembled flags. The flag is undoubtedly the perfect symbol of this – in my opinion, perfectly useless and ethically questionable – retreat into familiar positions. There is certainly bewilderment in the face of the planetary reconfiguration brought about by globalization – that is, by the telecommunications revolution – and lately I often say that those of us in the art world are lucky – especially thanks to surrealism – to be familiar with the possibility of the strange; the unusual, the incomprehensible, the disorderly, the irrational, or the random. And the wonderful. Thus, Manuel Velasco, who undoubtedly saw the modern utopia Imagine there’s no countries threatened, rebelled against walls and flags: he rusted them, scratched them, perforated them, thus arriving, perhaps unexpectedly, at a highly effective, sensual, and unique poetics of the industrial.

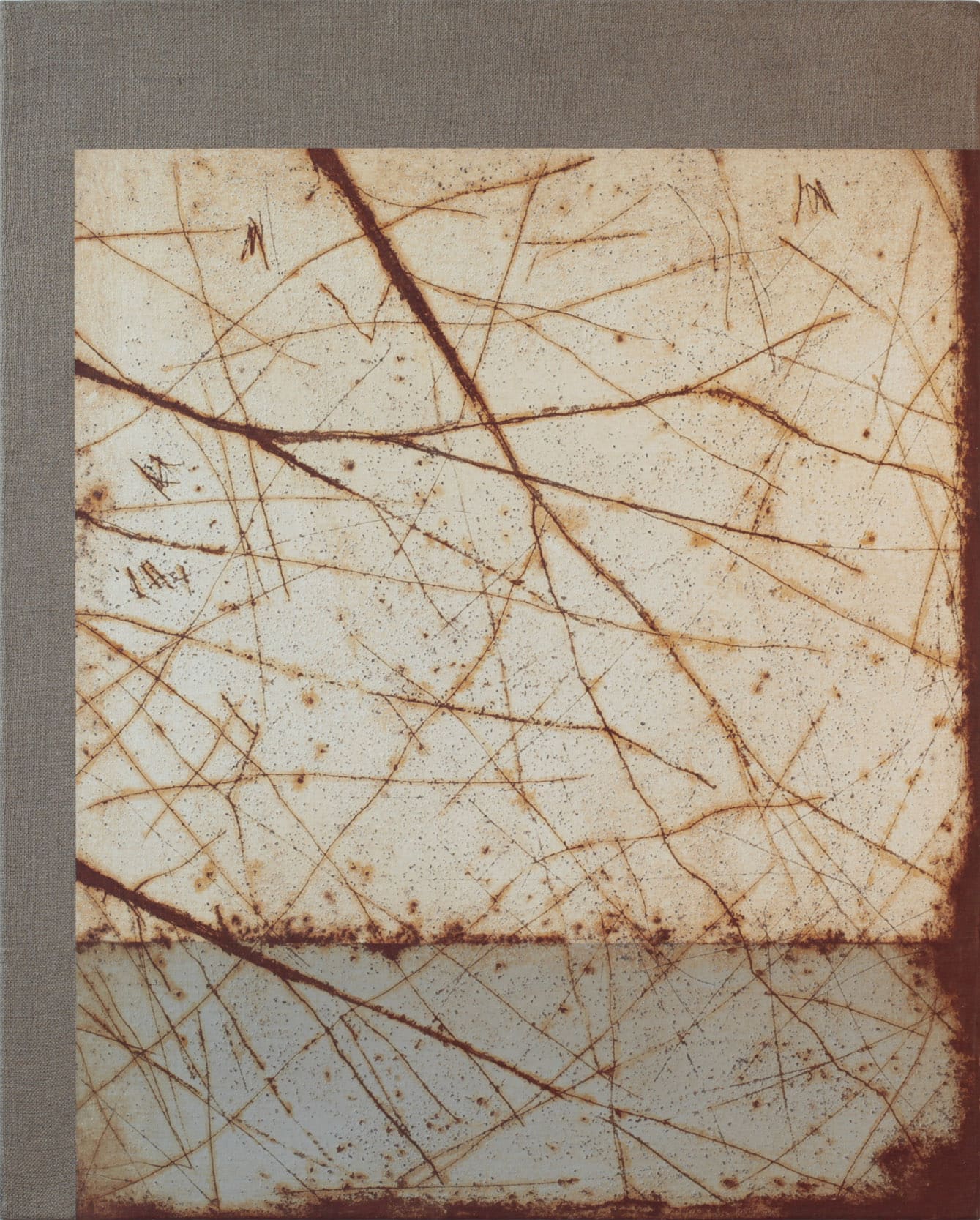

This artist, who in the early 2000s had taken advantage of new media to develop an interesting photorealism focused both on terrestrial and maritime landscapes as well as urban environments (paintings that were exhibited at the memorable Galería Almirante in Madrid and the prestigious Sala El Brocense in Cáceres, with introductions by Óscar Alonso Molina), turned to abstraction in the following decade and soon began developing procedures that are very much in line with the ones he uses now. At that time, the goal was to wear down the paint, add and remove layers, scratch and lift. Much has been written about these processes of accumulation and recovery; it is the mechanics of the ziggurat, the precursor of the pyramid, of the Tower of Babel, and, in a way, of the encyclopedia: it is that construction that rises on its own ruins, that accumulates its past and aspires to touch the sky because it gathers all known knowledge. In this construction, eternally excavated by researchers, just like in those paintings that seem like walls painted and worn down endlessly, evoking abstract landscapes, each layer refers to a specific moment (in addition to participating in the creation of the final image): the painting refers to itself, tells the story of its creation, and, by doing so, constructs a new image. Thus, there is the image, there is the landscape, but there is also the object of the painting, pure matter (probed). On this coexistence of ‘layers of reality’ – essentially the illusory and the real – Hoffman bases his classic theory of modern art: it is present in medieval art – the codices with their narrative, their illustrations, their gold-leaf letters, their filigrees – and returns with cubist collage, which combines the painted scene with newspaper clippings and other objects.

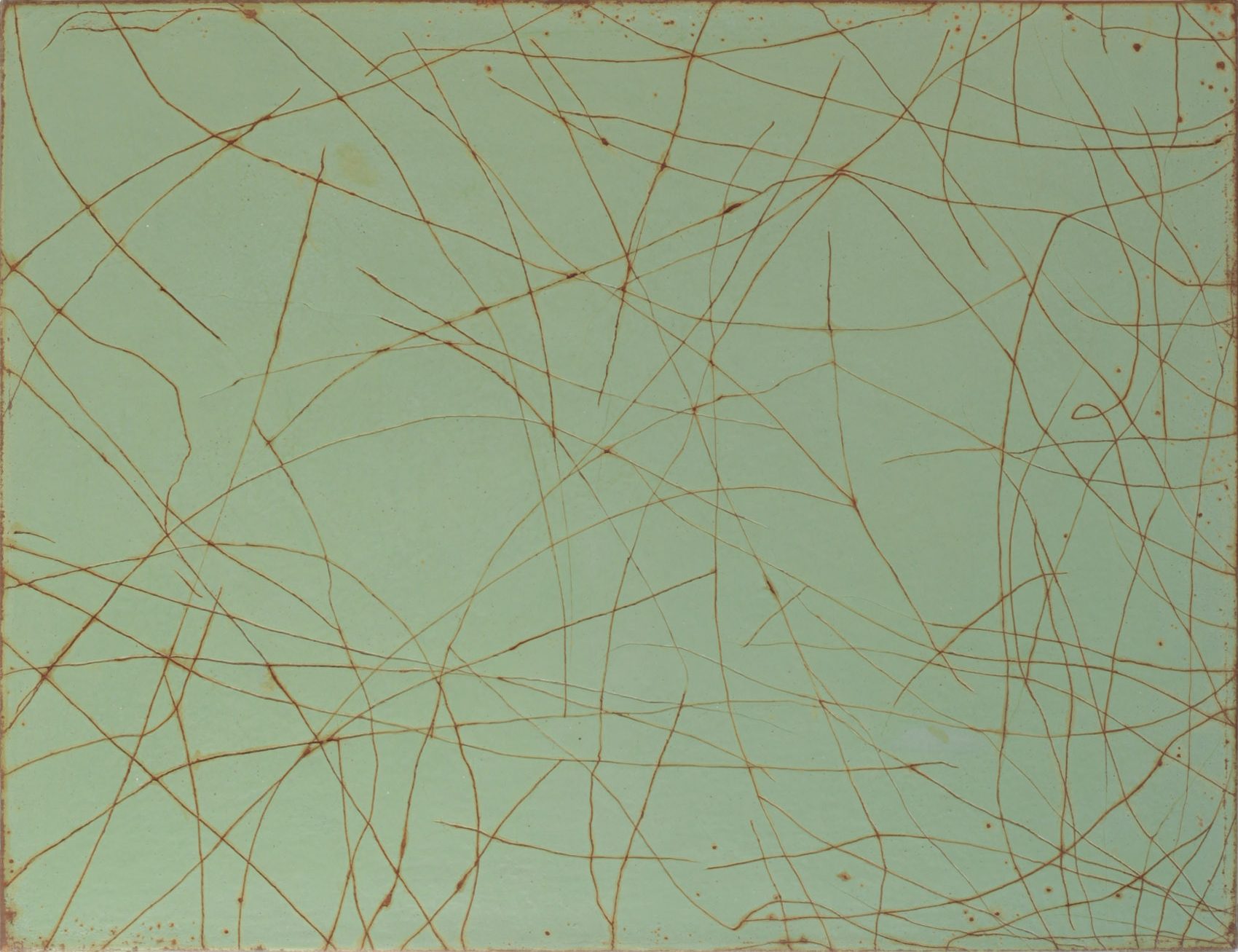

All of this is said because it is likely that Manuel Velasco, who, as we can see, has always evolved around the landscape (Javier Hontoria, the great critic specialized in landscape, wrote a text about him – and now he returns to it in a truly elegant manner), is in the best moment of his career. In these subtle, essential landscapes – with an undeniable oriental perfume – minimal, spectral in appearance among the remains of industrial material, there is, in addition to the evidence of his mastery in working with rust and color – Manuel Velasco has always been very skilled with materials, having invented several effective procedures – a new and wonderful element: the drawing. Lines that represent plants, forests, waters, and horizons without ceasing to be lines or, to be more precise, scratches that, without ceasing to be such, magically provoke the appearance of a space, a world, beyond the metallic surface. An Eden, the artist says, perhaps saturated, like all, by an unchecked development that leads nowhere (at best), which in this allegory of industrial twilight – far more beautiful, in that sense, than Houellebecq’s – takes the form of a hallucination. There are many more things in these beautiful paintings, too many to be counted – when an artist reaches maturity, they can no longer account for the multitude of elements that make up their work – the traces we leave – whose metaphor is the scratches, but also those drawings on paper made with the oxidation of metal objects – which have always obsessed the artist, the shadows and reflections, the tragedies of the world – ‘painting for harsh times,’ he tells me, the love for nature, the terrible climate problem, and Tanizaki, and Bosch, and Dürer… In any case, the formalist is only interested in those subtle and suggestive atmospheres created by the material when it is allowed to be, and those minimal, wise drawings, at once organic and geometric: it is the naturalness with which they emerge and construct the scene that guarantees the painting is true. We do not know what will come after the industrial civilization based on the burning of fossil fuels, but whatever it is, it is here, already sensed.

Javier Rubio Nomblot